The Keeper Of Traken

(Season 18, Dr 4 with Adric and Nyssa, 31/1/1981-21/2/1981, producer: John Nathan-Turner, script editor: Christopher H Bidmead, writer: Johnny Byrne, director: John Black)

Rank: 29

'Right everyone, never fear, I'm here to eradicate all evil. Wait you're not the Keeper of Traken! Why did you bring me here?'

'Well, you're not the Dr I was expecting either'

'What do you mean?'

'I'm the wicket-keeper of Traken - I invited the 5th Dr for a game or cricket!'

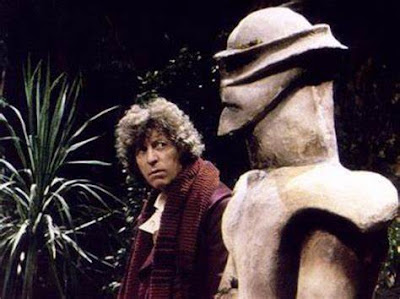

There’s a particular kind of melancholy that hangs around Tom Baker’s final trilogy of episodes that’s unlike anything else the show ever tried. We’re so used to seeing the 4th Doctor as the universe’s errant youthful joker that it’s quite a change seeing him stay quiet and still, old before his time on a trio of very downbeat stories. All three parts are very different to each other though and they’re all so good they’re all in my top thirty. In this middle story of the three he’s on the rebound after losing Romana at the end of ‘Warrior’s Gate’, not even bothering to make a K9 mark IV when she leaves either as if he knows that it’s time to come of age and put away childish things like robotic dogs. That last story found The Doctor struggling to adapt to a world that was moving in its own sweet time regardless of anything he did and where he had to be brave to say goodbye to his friends. By next story ‘Logopolis’ he’s reduced to watching his arch-enemy permanently wipe out half of the universe in Dr Who’s biggest (thankfully off-screen) bloodbath and losing his own life alongside it. By comparison ‘Keeper Of Traken’ is almost jolly, but only almost. After all, it’s a story that tries hard to find the good in all things but comes to the conclusion that evil will always survive even amongst good people, with a rare conclusion that sees the Doctor loses, wiping out his actions during this story and quite a few others. The 4th Doctor once seemed invincible, unstoppable, unbeatable, but now he feels as if he’s living on borrowed time, his quips coming from a dark and dangerous place, his flippancy a cover-up for his approaching sense of mortality, his dashing heroics not enough to stem the tide of entropy that is engulfing the whole world and turning it the wrong way. If most 4th Doctor stories are a party in space, as he takes out the bad guys with a wave of his scarf and an offer of jelly babies, then this is a wake.

Watching ‘The Keeper Of

Traken’ is quite the trip in 2023, so imagine how it must have felt in 1981,

against a backdrop of planet Earth swinging to the right and moving away from

peace to war. This isn’t a time for jokes and jelly babies, this is a new

decade that’s working to new rules, as if humanity has taken away the

stabilisers and the steering hand that had kept it out of harm’s way and the

feeling that, just maybe, if the rest of the 1980s carried on the same way as

its first year, then it might be humanity’s last. There’s a general air of

hopelessness and despair to the news bulletins around the broadcast of ‘Keeper

Of Traken’, as Ronald Reagan comes to power in America on a wave of

anti-Russian rhetoric and Margaret Thatcher prepares Britain for its first war

in nearly forty years, a feeling that the hippie hope of the 1960s and the

colourful glam denial of the 1970s have only delayed the inevitable state of

decay. Where does that leave a series that so neatly reflected the 1960s sense

of optimism and peace? It leaves it here, in a story about the Eden-world of

Traken, where the hippies won, where evil just calcified and shrivels up and

dies on contact with the planet surface (no, I don’t know how that works

scientifically either, but it’s a fairytale so you run with it!) and where the

planet has been kept safe for hundreds of years by a ‘Keeper’ and their

mysterious source of power, which feels like a metaphor for all those 1960s

values the series once stood for and where it started (as well as being a bit

postmodernist: the ending sees a ‘source manipulator’ plugged into the ‘source

of knowledge’, a good barebones summary of what’s going on with the plot). Just

look at the way the Melkur, the symbol of evil that arrived from another planet

and turned into stone is stopped by kindness and the flowers the people hang

round it’s neck: flower power values saving the world. Even the name ‘Melkur’

translates as ‘a fly trapped by honey’, killed by something sweet. Only now the

Keeper is dying, the empire is crumbling and even though the Doctor can put

things right for a single story it’s all undone with an ending that spells the

end for the planet, the empire and in the future very nearly the Doctor

himself. Despite the odd setting, despite the fact that right u to the present

day this is the very final Dr Who stories to feature no Human characters

whatsoever (Adric is Alzarian, remember), it all feels very familiar, very

Human, as if this the latest re-telling of an age old tale that goes back to

our beginnings, a tale of good and evil.

And if Traken, the one world in Dr Who’s that’s genuinely full of good

and kind and lovely people, can’t keep evil at bay then what chance have we?

The 4th

Doctor, who once belonged everywhere, doesn’t feel as if he belongs in this

story. He belongs to a different era, with quick-fix solutions to knotty

problems, and the world is in too much of a state to be put right quite as

easily and nothing is easy in this story, where pure good is no longer a match

for pure evil. That’s not to say that Tom Baker is wrong – far from it; the actor

may have been brilliant as the smart alecky alien (and I’m even more in awe of

his attempts to go ‘evil’ in stories like ‘Invasion

Of Time’) but he’s a far better actor than he was ever given credit for by

the world at large away from Dr Who. His work in these final days, when he

walks around like a timelord with the weight of the world on his shoulders,

shutting down even when talking to his companions (none of whom he knows very

well as yet) is sublime, going totally against seven years of what we’ve come

to expect. This final trilogy might well be his best work in the role in fact. To

be fair maybe some of it wasn’t acting: by all accounts Tom met his match with

new producer John Nathan-Turner who, desperate to make his mark on the series,

was happier to shout down his leading man than either of his two predecessors,

the clean sweep with the broom happy to call Tom’s bluff that he would leave if he didn’t get

his own way. The actor too was suffering from an undiagnosed complaint that

made him feel rough and grumpy (some fans have wondered if it was psychosomatic

but something in his metabolism changed – his famously long curly hair went limp

and straight so that what you see on screen is the result of hours in makeup

he’d never had to have before). Losing co-star Lalla Ward, with whom he’d had

so much fun (well, some of the time) also came as quite a blow – as much as

they continued their relationship away from the series, even getting married in

December 1980 right in the middle between the recording and transmission of

this story, it was rarely as happy for them in the real world as it had been

inside a TV studio with characters to hide behind.

I’m not sure whether

incoming script editor Christopher H Bidmead sensed these melancholy changes in

the world or in the rehearsal rooms or would have made them anyway but, after

sticking all the previously commissioned stories of season 18 that had been

partly started under predecessor Douglas Adams at the start of the season, here

at the end of the year he finally gets to shape Dr Who the way he wants – and

it’s a much darker, sombre, better series for it. Most fans add ‘scientific’ to

that list given that Bidmead’s background was in computers and his promise to

make Dr Who more ‘realistic’ in the wake of harder-edged scifi films like

‘Alien’ and ‘Close Encounters Of The Third Kind’ that were doing so well at the

box office at the time but honestly, other than the mathematics at the heart of

his own story ‘Logopolis’, that isn’t necessarily true: Bidmead’s take on the

Whoniverse in the stories he commissioned himself are even more fairytale-like

than Steven Moffat’s to come, full of planets that don’t strictly exist

(‘Castrovalva’) are filled with giant alien frogs archiving humans from across

time (seriously – ‘Four To Doomsday’) and giant pink Buddhist snakes (‘Kinda’)

not to mention Dr Who’s most surreal story ‘Warrior’s Gate’. After half a year

of big bold bright colours and bright spotlights the end of this season and the

start of the next is all about pastel hues, out of focus lenses and blurred

edges. The stories too are gentler and softer even though the stakes are

higher, more abstract stories about the concepts of good and evil that don’t

use guns and weapons and sword fights so much as imagery and metaphors. And no

story is more fairytale-like than ‘Keeper Of Traken’, which feels like a

Brothers Grimm style folk tale, where a people who live in paradise on a planet

powered by a mystical unseen source of energy give in to their darker side.

This is a world that has been without evil for so long that people have

forgotten to be afraid of it and think they can always beat it, but they can’t:

good and evil have always existed side by side and always will exist in balance,

because you can’t have one without the other, and after periods of light there

are also periods of dark. Note the way that the ‘goody’ and ‘baddy’ swap positions

by the end of this story, where the shrivelled up old man and shrivelled up decaying

Master in parallel, only The Keeper starts with all the power and The Master

tries to end with it (the true balance is in the middle, when The Doctor

intervenes, a character whose neither all good or all bad).

Bidmead’s starting point

for this story was an unusual one for a Dr Who story forget your science

weeklies, your scifi pulp magazines and your children’s comics, it was an article

on the Christian concept of millennialism, the belief that civilisations always

went in cycles. Mankind would always get it together for a short length of

time, just long enough to believe that a time of longterm peace and prosperity

was possible, but that longterm any one thing was unsustainable. Peace and

stability were fragile and something would always come along and puncture it

when we had become too complacent and were looking the other way, whether a

natural disaster we couldn’t control or from our own hand (after all, it’s

harder to be scared of a war when you’ve never lived through one than when

you’ve survived one and vowed never to risk another). Though technology might

change and the rulers who sit in the big throne might regenerate and change

their appearance mankind never changes and each successive generation are

liable to make the same mistakes as their forebears. There has to come a point,

after all, when we stop evolving and start devolving – there must be a limit

humanity can reach somewhere, some shelf life when the civilisation we’ve built

for ourselves can’t maintain itself any more and crumbles. And what better a

time for that to happen than a year of great change, with a big fat ‘zero’ at

the end of it, or maybe a few? Specifically ‘Millennialism’ is the fear of the

end of a millennium and the start of a new one, something that’s in all sorts

of ancient texts (including the Bible) and in 1981 times was getting pretty

close to the year 2000; so many changes had already taken place with the start

of a new decade, what on earth would the start of a new thousand year cycle

bring? Of course to those of us sitting

here in the 21st century the idea of the year 2000 being at all

scary is patently complete and utter nonsense (the impending doom and imminent

collapse didn’t start until at least, ooh, 2001) but it was a real fear that a

lot of people shared. To quote Kassia, ‘nothing is normal at

such a time’. It’s a very Dr Whoy theme, then, this question

of balance, of how you can’t have good without evil or hope without despair,

happiness without sadness or victory without failure. And after seven years of

running around putting things right effortlessly even the 4th Doctor

must fall.

Given that idea of good

versus evil and a panic over the future you’d have expected Byrne to go down the

route of snakes interrupting the garden paradise, especially given that the

Mara are waiting in the wings four stories later, but instead he creates The

Melkur, a stone statue that’s ‘alive’ and welcomed into the garden by the kind

noble people of Traken. Everyone there knows the Melkur represents evil, but

legend has it that Traken was just too kind and pure a planet so evil just

shrivelled up and died when it arrived there, the Melkur ending up a calcified

statue unable to move. It’s become a monument down the centuries, a reminder

of darker times, and the locals still employ a girl every generation to look

after the statue and feed it, to make it welcome and feel a part of the planet.

If this was a Dr Who story in any other era that would be karma enough for

everyone to stay happy and safe: you can magine one of the black-and-white

comic strips having the 1st or 2nd Doctors turn up, talk

about how marvellous it all is, exterminate the Trods hanging around outside

and go home. You think for one glorious episode as if there’s not going to be

any peril at all in this story and that the ‘Keeper’ who called on the Doctor

for help with a distress call has simply got things wrong– if anyone’s an

antagonist in the early part of this story it’s the Doctor, arriving in the

Tardis and swishing his scarf around noisily, ruffling feathers amongst the

Traken nobles as much out of boredom as anything else (or perhaps to have a

break from Adric asking him endless questions over and over again). It’s fun to

see the Dr greeted with the sort of resigned diplomacy reserved for Great Aunts

and rogue politicians rather than as an all-conquering hero as a change and its

almost a shame when the Melkur starts to wake up and The Keeper’s sixth senses

of a ‘lurking evil’ prove to be true. And even then it’s a subtle evil: I mean,

the baddy is literally rooted to the ground, he’s not going to cause any real

trouble is he? But evil has funny way of getting inside people without them

really noticing, slipping through the cracks of the people in Traken who haven’t

known evil for so long they’ve forgotten what it looks and feels like. Forget your mass alien invasions, this story

is subtle in the extreme, with a nagging sense of something slightly wrong

rather than a horrific tragedy, and in a season that started with mafia lizards

playing tennis and talking lifesize cactuses is all the better for it. Of all

the planets that exist in the Whoniverse Traken is in my top places to move to

(err, give or take – spoilers – the fact that it’s destroyed in the very next

story!), a place where everyone is kind and helpful and benevolent, without

losing any time or resources playing silly soldiers, so that it’s had time to

create multiple wonders of its own (I love the way that despite this being such

a spiritual planet, Traken is no slouch when it comes to technology and has

things that even impresses the Doctor). Which also means that it’s a place

totally unprepared for anyone who wants to do them harm. It reminds me of my

days happily playing the computer game ‘Age Of Empires’ and building Ancient

Greece into a bastion of knowledge and learning. Only for my friends playing as

Ancient Romans and Vikings and the like to come along and smash everything up

(*sob*!) If ‘Traken’ is a story about anything then it’s a story about balance,

about how societies have to be a bit of everything to survive otherwise people

will take advantage of you, which is a hard lesson to learn but is sadly true.

The hippie philosophy

also makes this a story that, more than

any other in the 1970s and 1980s I can think of, seems like Dr Who’s roots in

the 1960s, where it started. Many fans have commented that ‘The Keeper Of

Traken’ is ‘like a Hartnell’, which might explain why I love it so much (the

1st Dr’s being my own particular favourite era, with a greater sense of magic

and wonder and endless possibilities than any of the others and a large dollop

of 1960s spirit and optimism) but for most reviewers that’s shorthand for

‘slow’ and they leave it at that. ‘Keeper’ is decidedly slow, full of characters

either so old or so at peace they don’t move very much and do a lot of talking

at each other, without the usual running up and down corridors, but that’s a

good thing when the dialogue is this good and involving: just take a look at

the ‘Internet Movie Database’ site for this story where there are more quotes

taken from these four episodes than pretty much any other Dr Who story. An even

bigger reason this feels like a Hartnell story is that we have time to explore

this world, that Traken isn’t a planet that only exists for the purposes of the

plot and has no life beyond it – there are a lot of scenes giving us things

that, strictly speaking, we don’t need to know to follow the story but which

really help give us the feeling of a world full of customs and traditions that

existed long before the Tardis arrives. It feels ‘real’, a planet that

beats to its own eternal logic that’s almost but not quite like ours, full of

small subtle detais that really sell this world and (rarer than you might

think) proves that writers, script editor and director were all on the same

page: the same lush ‘fairy dresses’ in un-crumpled velvet as if the Trakenites

have nothing better to do all day than iron; the fact that every female on this

planet genetically has curly hair (even Nyssa, which is a problem when she

becomes a companion later and Sarah Sutton has to spend hours getting her

naturally straight hair made up every time) and the men all have straight hair,

the way everyone keeps their voices quiet and respectful, even in anger (such a

contrast to all the usual shouting!)

Another is that ‘Traken’

is very much of its time, the way the 1960s episodes often were – for the most

part 1970s Dr Who has been about escapism, the Doctor’s exile to Earth

replacing the sense of exploring current affair in metaphors in space and while

we’re about to get lots of cold war parables when the 1980s hits its stride this

is kind of a halfway house, one that looks as if the camera is about to cut

away to ‘Spandau Ballet’ or ‘A Flock Of Seagulls’ performing in front of the

Trakenite extras in their velvet ruffs.. Most of the landscape has the same

sort of lushness as contemporary TV (we’re still a little early yet for the

‘Beauty and the Beast’ series but it looks just like that, with just a hint of

‘Knight Rider’) and people who live on Traken have that same sense theatrical

dress sense and gothic makeup, seeming like they write poetry about death in

their bedrooms at weekends after a week’s heavy pouting, even though they’re

quite happy people most of the time. Like all good new romantic somethings

though there’s just a hint of the punk rock Melkur that came before them that

everyone’s reacting to (an era entirely absent aesthetically from DW, the

closest being the back-to-basics everybody-dies horror of ‘Fang Rock’ – and

that’s a story about an alien green blob killing people in an Edwardian

lighthouse so it’ s not exactly a perfect fit; the drug-dealing ‘Nightmare Of

Eden’ is another candidate but if anything that’s an anti-punk story about the

dangers to your Mandrils if you keep stuffing things up your nose). This is a

planet of people who’ve seen their elder siblings get their hands dirty in the

muck and grime and slime of the universe’s underbelly and decided that they’d

rather live above it all, pretending to be nice to each other (even to visiting

aliens: honestly most other planets would have kicked the Doctor out given all

the problems that follow after he arrives). That’s the key word though,

‘pretending’ – Traken lives in fear that one day evil will come back and rather

than be above it all really everyone in this planet has got their fingers in

their ears going ‘la la la I can’t hear you’ and talking about how merrily

happy everyone is all the time in the hope that if everyone says it enough

they’ll believe it. I can’t decide whether this is a genuine catty comment from

a Dr Who production team laughing at their core youthful audience of the day

for lapping all this up in the early days of Thatcher and strikes and poverty

(the way ‘The Abominable Snowmen’

in 1967 laughs at hippies for trusting disembodied voices promising them

‘answers’ and ‘The Dominators’

dooms them all because pacifism is stupid) or whether it’s simply Dr Who doing

its old tried and tested template of showing that it’s impossible to have good

without bad, that as long as humans (and even their Traken near-cousins) are

around we can never have true paradise (or pure dystopia) because there is good

and evil in all of us and so therefore in our societies too. Sometimes ‘Traken’

feels existential despair on the writer’s part that we can’t have nice things

because life doesn’t work that way – and sometimes it feels like a warning not

to look the other way and ignore the danger signals like we once did because

bad times will happen again if we’re not careful. It might be significant, too,

that the Melkur is designed (and indeed described in the script) as being

rococo, from the ‘roaring twenties’ when the world partied away the years

between the two world wars trying to pretend that everything was alright again,

ignoring Hitler’s rise to power and the great depression (they would have been,

roughly, the grandparents of the children watching this the first time round). Designer

Tony Burroughs picked up on this with his sets, too, modelling them on the work

of the Spanish architect Gaudi whose work was most famous in that decade (think

Barcelona’s Cathedral), wanting the feel of a planet that had been hewn out of

rock and had been there for centuries (they look magnificent: Burroughs is,

deservedly, the only Dr Who set designer to go on to win an Oscar, for the 1997

film ‘Richard III’). Dr Who is briefly back to its origins as a multi-generation

family series then, for a whole new generation – if only they’d kept this up

into the 1980s and beyond!

I have another possible

theory too, which links in to that 1920s feel: ‘Traken’ was produced at the

height of the cold war when tensions were growing again and while Dr Who was

forever switching sides whether capitalism or communism was better this is a

story that feels firmly on the latter’s side. Only what we had in Russia by

1980s was not communist in its purest sense, but a dictatorship takeover. We

never fully got to see what ‘pure’ communism in the Lenin sense might have

looked like, a world where everything was roughly equal and where everyone had

their roles picked for them due to their abilities (nobody on Traken so much as

mentions money and everyone is only too happy to fulfil their responsibilities

and do what they’re told because the state knows best and is working to a

‘higher’ power’: indeed, the first sign for the elders that Kassia might be

‘evil’ is when she looks upset at Nyssa getting her job tending graves and

calcified statues). Leninist Russia following the October Revolution wasn’t

paradise but it was getting there: compared to the years under the corrupt

Royal family, when the rich were well fed and everyone else suffered it was a

far kinder, friendly place to live. Only Lenin died in 1924 when communism was

still fragile at best, without a natural heir: he’s surely the Keeper, the

interpreter of this great bountiful knowledge with a vision no one else shares

as fully. Trotsky seemed the obvious candidate to take over, the mild-mannered

protégé, ut he couldn’t command the crowds with the same charisma: in this

story he’s Tremas, felled not with a pickaxe to the head exactly but a blow

from inside a grandfather clock (don’t ask!) The Melkur? That’s Stalin, a being

that barely moves a muscle and tries to pass himself of as a friendly Uncle,

whose secretly plotting to take all the best things for himself even more than

the Royals did, ‘communism’ equality by name but no longer by nature. Only

Stalin was clever enough not to rule in a giant coup or by necessarily

denouncing his rivals but in quietly moving into power, bit by bit, until he

was in a position where his own people began to think of him as the good guy.

‘The Keeper Of Traken’ is George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm’, then, only with aliens in fancy dress and statues rather than

talking horses and pigs (‘Two Calcified Legs Bad…’) Given The Master’s links to

this story, maybe that’s why he felt so at home singing ‘Ra-Ra-Rasputin’ in

‘The Power Of The Doctor’? (There’s certainly no other excuse for that scene I

can think of…)

Another reason this story

feels like a Hartnell is that the supporting characters are just so good: Denis

Carey makes the elderly Keeper very different to his other Dr Who role, Who’s

best dotty professor Chronotis in ‘Shada’. He’s kind of The Pope, an elderly

figure that knows they’re going to die in the job but sees being plugged into

spirit as the greatest thing they could be doing with their life. Sweet and

innocent Kassia would have made a worthier companion even than her

step-daughter Nyssa and it’s a shame she gets bumped off so early on – as much

as she’s the de facto ‘baddy’ for the story, often characterised as an ‘evil

stepmother’ (like the fairytale theme of the rest of the story) really she’s a

kind person easily swayed; she becomes brainwashed by Melkur slowly, in waves,

when her biggest crime was trying to tend it’s grave with flowers. Jealousy is

her downfall, as it so often is in fairytales: she looks in the mirror and sees

a step-daughter prettier than her getting her favourite job, while facing

losing her husband to his life connected to source as the next Keeper, losing

the two things that keep her happy – it’s a natural and very Human re-action

for a Trakenite to be upset about but it’s enough ‘badness’ to let The Melkur

do its thing. Brainwashings in Dr Who are two a Movellan Knut, but

this is about the best in the series’ long list of them: you see Kassi’as mind

wrestling with what Melkur tells her, unsure which view is right, desperate to

do the right thing, but the more she argues the further she goes from her true

pure self and the greater hold the master has over her. Kassia is controlled partly through her necklace:

Byrne was inspired by Irish mythology and the ‘Jodhan Moran’, a bewitched

collar that would kill anyone unfair or unjust and worn by a judge as proof of

his kindness and mercy and that all his decisions were ‘right’ – only, in Dr

Who, it’s used in reverse, as proof that even the nicest person can be

corrupted. Kassia is a tragic figure, even more than her husband and daughter

and excellently played by Sheila Ruskin. The Traken elders are very believable:

old men who aren’t used to change and want things to stay the same, each one

with a slightly different plan to take over but not sure how. Their

disagreements with each other actively scares them in a way we’ve never seen in

this story, because under the old Keeper nobody disagreed about anything

(again, this is Leninist Russia in the aftermath of his death). Of particular note are John Woodnutt as Seron,

who continues to be one of Dr Who’s most reliable actors with several different

roles to his credit and Robin Soames as Luvic, who was so perturbed at not

having many lines that he decided there must be a reason he was the quietest

Keeper and invented a stammer in rehearsals (JNT made him take it out!) – he’ll

make the most of a similarly insubstantial role as ‘Chronolock Guy’ (that

really is the credit, not a description!) in ‘Face

The Raven’. You have to feel for poor Luvic: he’s the King Charles of the

Dr Who world, someone whose waited his whole life to be Keeper while his

long-lived predecessor takes over, only for events to mean he sits in power for

all of a day!

And then there’s Anthony

Ainley, who starts off as Nyssa’s gentlemanly father Tremas, upstanding and

sweet and just a little bit crotchety (he’s the 1st Doctor all over again, but

specifically the later 1st Doctor whose softened considerably by his last

stories) and then in the last daring closing minutes becomes (mega huge

spoilers that will ruin everything if haven’t seen the story)...the regenerated

Master. He wasn’t in Byrne’s script at all (he was a new figure, a megalomaniac

named Mogen) but Bidmead had been pushing to have The master back, to give the

Doctor a regular foe again and was already half-thinking of bringing him back

in ‘Logopolis’ – rather than have two similar characters back to back, though,

why not make them the same? Byrne was only too pleased – he’d liked The Master

and might have used him himself had the character been around. But weirdly, and

uniquely, The master is played by someone else for most of the story and Ainley,

who played The Master for more years than anybody, mostly plays another part in

this story. At first we see the emaciated version we see in ‘The Deadly

Assassin’ at the end of his 13 lives and it has to be said that ‘Traken’ is a

neat mirror to what happens later to Matt Smith when the Doctor reaches the

same age in ‘Time Of the Doctor’, only instead of invading a peaceful planet he

defends it from evil getting in. And then, after Tremas gets a bit too curious

with The master’s Tardis (oh that curiosity!)The Master takes over Tremas’

body. We’re a little bit robbed of that shock twist nowadays when chances are

everyone sees Ainley in costume and assumes Tremas is the Master all along (and

let’s face it, the anagram name is a bit of a giveaway given what they do every

time The master returns during the JNT years). That’s all in the future though:

serious brownie points to anyone who saw that shock twist coming on first

transmission because it really does come out of nowhere, at the point when in

any other story the Doctor would have ‘won’ and things would have been put

right. It really helps make ‘Traken’ feel more than just another Dr Who story:

it’s an inescapable fate in a story all about how you can never take defeating

evil or goodness for granted.

What’s more, unlike most

Dr Who twists that tended to be destroyed by leaks or Radio Times write-ups

they managed to actually keep this one quiet. ‘After all, following Roger

Delgado’s untimely death most fans thought they would never see the character

again and even when he came back in ‘The Deadly Assassin’ he was a husk of his

former self who really didn’t act much like The Master: it had been eight years

since The Master had been seen properly. The irony, fully in keeping with the

rest of this eerie story, is that the takeover couldn’t have happened to a

nicer guy, someone whose so pure that he couldn’t even conceive of the Master’s

grandfather clock being a Tardis-size trap (good life advice: never investigate

a surprise materialising object that ticks). It’s a colossal tragedy for

Tremas, for Traken (destroyed by The Master next time out), for the Doctor (who

regenerates indirectly because of The Master’s masterplan) and for the universe

(a lot of which is unceremoniously wiped out in ‘Logopolis’). Anthony Ainley

was a man with so many Who connections its amazing he hadn’t been in the series

already: he’d come to fame partly through his star turn in ‘Out Of The

Unknown’, BBC2’s highbrow scifi response to Dr Who on BBC One, where so many of

the production team worked, he was the illegitimate son of themed thespian

Henry Ainley who was very close to the Pertwee family (and was in fact Jon’s

Godparent) and his brother was Tom Baker’s one-time drama teacher and

room-mate. For my money he’s also one

of the best actors who was ever in Dr Who, under-appreciated only because Roger

Delgado as the ‘original’ Master was one of the absolute best – later stories

will reduce his Master to a pantomime baddy doing bad things because he’s

naughty, but here with a decent script behind him (and again in ‘Logopolis’ and

final story ‘Survival’) Ainley’s one of the greatest threats the Doctor ever

faces, driven by several centuries of being trapped in a statue plotting

revenge with nothing to keep him alive but thoughts of cruelty and every bit as

bad as the Doctor is good. And Tony is even better as Tremas, one of the

gentlest of men we ever get to meet, with Ainley given as real chance to show

off his full range in this story – it’s hard to believe that the close ups of

the two pairs of eyes at the end, merging as one, is even the same actor, given

that one is full of fading warmth and the other ice-cold growing in power. It

is, however, a whacking great coincidence that The master just happens to take

over someone whose name is an anagram of his own, almost as if this were a

blatant clue in a long-running science-fiction series rather than something

that was ‘really’ happening…

Interestingly Ainley

doesn’t play The Melkur voice even though would seem the most obvious (and budget

saving) thing to do: instead its Geoffrey Beevers, whose all too believable as

the presence of pure evil even though he has nothing more to use than a few

whispers – he’s so good at it that it’s sad we didn’t get at least a season of

stories of him as The Master (he’s excellent as Big Finish’s Master of choice

too, filling in the gaps between ‘Deadly Assassin’ and this story; in real life

he was married to Liz Shaw actress Caroline John and its one of my great

regrets they were never in a Dr Who story together before her untimely death,

even on audio). The Melkur is a great concept: a statue of pure evil that’s

been rooted in place, but can still create influence and overcome the whole of

Traken, despite the fact that they can just walk away from it. There is, so we’re told, a whole planet of

Melkurs (one we visit in Big Finish audios but never on screen) and the Trakens

used to be scared of them but not anymore in their Garden Planet Eden. They

don’t even consider it a threat until it’s too late. The Melkur lets the story

ask big questions, too, about mercy and kindness being misplaced in a world

that doesn’t respect them: if ‘The Mind Of Evil’ is the Dr Who story that

pushes the point for the rehabilitation of prisoners, of showing patience to

people who fell into bad times and made mistakes by giving them a second chance,

then ‘Traken’ is the story that makes the case, if not quite for capital

punishment, then the idea that some beings are too evil to ever be allowed near

your loved ones again, no matter how restricted and trapped they seem to

be.

Given the feeling of doom

and gloom that hangs over this planet (a rare story where the Dr seems to solve

everything, then it all unravels again when he leaves, as if even our hero’s

morals aren’t enough to stop pure evil) it’s no surprise that Traken is the

only named planet we recognise that’s in the half of the universe that gets

wiped out in next story ‘Logopolis’ (a story which builds on directly from

events here) – my one big fault with this story isn’t even with this story at

all but the fact that nothing else really comes from it. Nyssa should hate The

Master with a burning fury never seen in the series before. Not only does he

have the nerve to wipe out her planet and everyone she ever knew before meeting

the Doctor and Adric, he has the audacity to walk around in her father’s body

while he does it, those kindly features contorted with hate. Combined with

Tegan who’ll have her own beef with The Master in the next story (shrinking her

Aunt Vanessa down to size in the opening minutes) I would have loved to have

seen the new Who girls club together to bring The Master down to size

somewhere, perhaps with the new merciful 5th Dr looking sad over in the corner

seeing the bigger picture and trying to stop them while talking about mercy.

Instead Nyssa barely bats an eyelid when she meets The Master again in

‘Logopolis’ and ‘Timeflight’, as if this story never happened. This could have

been the single biggest companion-driven bit of drama in the series and would surely

have been a natural place to take the series had Bidmead stayed on: alas the

script editor’s already got cold feet and is getting fed up of clashing with

the producer so as well as being nearly his first hurrah it’s almost the last

he oversees from start to finish. And Johnny Byrne’s second story ‘Arc Of

Infinity’ is mucked around with so much it doesn’t feel like the work of the

same writer at all. There never was a second ‘Traken’, because pure good runs

of Dr Who can seemingly only sustain themselves for a little while. That’s a problem for the future though: as a

story taken on its own merits ‘Keeper Of Traken’ is a lovely little four-parter,

Dr Who’s prettiest and most beautiful tale in so many ways (until it abruptly

isn’t), an old fashioned tale of trust deceit and betrayal and how thinking all

the nicest thoughts in the universe won’t be enough to stop evil when it really

wants something, dressed up in contemporary clothes that makes it feel new and

up to date (or did at the time – although even then it seems like the most

ageless, timeless 4th Dr story in so many ways). Yes it could have done with

something more perhaps, a sub-plot or three and we never fully get to see

properly how peaceful Traken is before the Melkur arrives (some people walking

round smiling and handing out flowers isn’t quite the same thing). By and large

though its as close to perfect as you’re ever going to get: it’s a good story

for the Doctor, a great one for The Master, a highly promising one for Nyssa

and has a feel all of its own that makes it unique in the Dr Who canon, that

does something different with a planet full of good people rather than bad as

usual. There’s so much to love about this story, from the costumes to the sets

to the acting to the writing and a rare story where every department deserves

applause and no one messes up anything much at all, no one! But especially the

writing: there’s a\ poetry to this story (Byrne did indeed start life as a beat

poet), a word choice that makes the characters, the planet and the dialogue all

sing with a beauty few other Dr Who stories can match. While not too much

happens before the shock ending nothing much happens with such grace and style

that you can’t help but be entranced. Would that we had more Dr Who stories

this lush, this pretty, this poetic, this thoughtful. Much under-rated.

POSITIVES + The Melkur

statue is gorgeous and looks even more like something from 1981 than the planet

and actors’ costumes do. After all this was an era where its heroes and

heroines liked to stand still and stare vacantly down the camera with an

existential shrug, perhaps with an occasional arm wave. What better way to

represent that than with a statue and one that really fits the aesthetics of

the time, like ‘The Wicker Man’ crossed with the Tin Man from ‘The Wizard Of

Oz’ but with a very 1980s shape and design on top. The moment when The Melkur

finally moves, just when you’re convinced yourself it’s a prop not a costume,

is properly scary Dr Who and all the more so for coming in the middle of what’s

been quite a gentle and placid kind of story.

PREQUELS/SEQUELS: ‘Guardians Of Prophecy’ (2012) is

Johnny Byrne’s intended sequel to ‘Traken’ which was intended for the 5th

Doctor in 1983 then re-written for the 6th in 1984 before being

dropped – the latter version ended up as part of series three of Big Finish’s

‘Lost Stories’ range (2012). It’s a good one, featuring the last few stragglers

of the Traken empire who survived the events of ‘Logopolis’ and set up a new

home on a planet they name ‘Serenity’. There’s a division though: do they try

and make this planet a new Traken or do they overthrow their elderly elect and

become more like other planets? Politics spill over when a thief is caught and

sentenced to be thrown into a labyrinth (yet another one in Dr Who!) In a

(spoilers) twist it turns out that the agitators have been stirred up not just

by one Melkur but dozens, all of whom have been living on the planet and who

have the ‘psychic power’ to pull the Tardis out of orbit as it flies past;

they’re the ‘real’ thing, not The master in hiding this time. Along the way

there’s scares with robot guardians, a living computer named ‘Prophecy’, a

‘shield of goodness’, and arguably way

too many expensive ideas to be done properly on a Dr Who budget in the 1980s,

one of the reasons the story was reluctantly dropped. On audio though it’s

another matter and like the majority of the ‘Lost Stories’ range the result is

way more interesting than most of the stories that actually made it to screen

that decade.

Previous ‘Warrior’s Gate’

next ‘Logopolis’

No comments:

Post a Comment