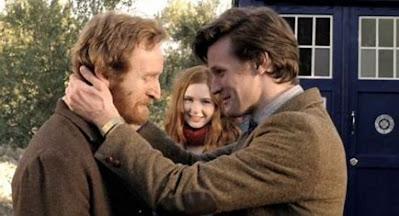

Vincent and The Doctor

(Series 5, Dr 11 with Amy, 5/6/2010, showrunner: Steven Moffat, writer: Richard Curtis, director: Jonny Campbell)

Rank: 157

'Well, that was an odd exhibition. Silurians in Monet's 'Lilypads'. Turner's 'Burning Houses Of parliament' with Terrileptil lurking in the background. Multiple Mona Lisas with 'this is a fake' written on the back. 'The Scream' featuring Bonnie Langford as Mel. Whistler's 'Are You My Mummy?' Actually 'Church At Auvers With Krafayis Alien Waving In Window' is the most normal painting here!

The Dr Who world was shooketh when Steven Moffat managed to rope his old writing colleague Richard Curtis into writing an episode, easily the biggest name writer the series had had so far. Especially those of us with memories of the Comic Relief night of 1999 when Moffat wrote ‘The Curse Of Fatal Death’ Dr Who sketch at short notice and Richard Curtis was on record as saying that he’d never actually seen it. Moffat had become involved as his wife, Sue Vertue, helped run the charitython and she had suggested a sketch her hubby could come up with at short notice – Curtis had enjoyed himself and getting in contact with lots of old friends from the movies and left Moffat the passing message ‘I owe you one’. Now that Moffat was showrunner he decided that time was now and asked for a storyline, hoping for one of those very British type comedies he was famous for. He was surprised and more than a little bit nervous when he got the call back ‘Alright, but can I make it a story about depression, madness and suicide?’ Moffat mumbled something about Dr Who being a family drama on at teatime and crossed his fingers. He also sent some of his favourite Dr Who stories to watch, which Curtis did with his two children over the fortnight he wrote the first draft of what became ‘Vincent and The Doctor’. Everyone was surprised by what came back. For what nobody really knew about Curtis was that he was a big fan of Van Gogh’s work. He’d taken his children to the ‘real’ ‘Muse D’orsay’ art gallery in France that houses the biggest collection of Van Gogh paintings (alas only twenty: so many were lost, thrown away or burned; sadly the one in the series is a re-creation in Wales but a pretty close one it has to be said) and went back again for research. Curtis had long been fascinated by Van Gogh’s story: a painter who became celebrated only after his death, who only ever sold the one painting in his life (and then to a family friend). He’d found himself walking round the gallery wishing that there was some way he could get a message to the artist that he would be remembered and that all his suffering he’d gone through to make his art had been worth it. Richard had even half-heartedly tried to make a film or a TV project about it on and off for fifteen years. Then Moffat came along with an offer to write for a time-travelling series and the opportunity seemed too good to refuse (Curtis joked to Dr Who magazine that Moffat had gone back in time and planted the idea in his brain until it was ready for hatching right when he needed. Which shows if nothing else that he ‘got’ the Dr Who stories he watched!)

We still waited anxiously to see which Richard

Curtis we would get: would it be the clever thoughtful insightful writer of

‘Four Weddings and a Funeral’ (where Simon ‘Charles Dickens’ Callow makes

everyone laugh for half the film then cry, though it’s really stolen by

Charlotte Coleman not long before her death, the little girl who starred

alongside Jon Pertwee in ‘Worzel Gummidge’), the clever timey wimey writer of ‘Notting

Hill’ or the lowest common dominator one of such broad and unwatchable comedies

as ‘The Vicar Of Dibley’ and ‘Mr Bean’?

Frustratingly this story ends up being a little bit of all three. There

are fans who will talk passionately about how this is a moving tale of

redemption that’s brave enough to treat mental illness with the seriousness it

deserves (especially in a series where ‘mad’ people tend to be villains and

monsters, not painters while only the similarly brave ‘Waters Of Mars’ has a suicide central to the

plot while only ‘Kinda’ in 1982 had gone

anywhere near madness properly and that’s in a metaphorical symbolic way) and

there are many scenes here every bit worthy of those accolades, especially the

moving ending. There are others who will talk about how clever it is to have a

story that uses time travel so well, of having Amy especially suggest all sorts

of paintings that came later (the best gag of the episode: Van Gogh doesn’t even

like sunflowers and paints them only to please her!) But there are other times

when this moving emotional story is a bunch of comedy scenes filled with the

most awkward stilted dialogue (‘Art can wait, this is life and death’. Doctor,

you’re talking to a painter – art is life and death!), not to mention the truly

bizarre scene where some respected actors waving their arms in the air as they

fight off invisible monsters. There are fans who say ‘Vincent’ is the best Dr

Who episode every made. There are those who say it’s the worst. They’re both

right, at different times, in an episode where more than possibly any other in

this book the quality is all over the place.

Let’s start with the positives: Curtis’ heart is

clearly most invested in the moments when Vincent finds out that he’s not the

loser everyone thinks he is. While Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare and

Agatha Christie all asked variations of ‘will my books last?’ they were all, to

some extent, legends of their own time generation and zipcode at the time they

were in the story. Vincent spends the entire episode thinking his new strange

friends are laughing at him because what has he ever done with his life? It’s a

sad tale: he only found fame and acceptance in death, when it was too late. So

we end up with is a story that works differently to every other Who historical

based around a celebrity. Society generally paints famous people in

black-and-white terms, something that often gets Who in trouble when it tries

to whitewash the bad (see Churchill in ‘Victory

Of The Daleks’) or ignore the good (‘Demons

Of The Punjab’) for a simplistic episode that offends people who know the

facts and passes on the wrong message to those who don’t. The best Who

historicals though show people who are a realistic mix of good and bad,

presenting us with our fixed idea of who they are but filling in the gaps of

who they actually were (Marco Polo, Richard the Lionheart, Charles Dickens,

Agatha Christie). By and large we see these famous people, who we see every day

in reverential documentaries and on banknotes and stamps, as ‘real’ people

again, often before they were famous and being treated as ordinary, taken down

a peg or two. Usually we see a somebody back when they were a nobody, but

‘Vincent’ has a unique take: a somebody near the end of their life who still

thinks they’re a nobody. Those are the scenes that work best because they come

from the heart. Especially the best scene where The Doctor takes Vincent to the

art gallery in 120 years’ time where there’s a full exhibition of his works and

the curator (played well by Curtis’ regular Bill Nighy, an actor often assumed

by the papers to ‘be the next Doctor due to his playing similar eccentrics and

who asked that his name not be included in the publicity, as he didn’t feel

he’d done enough to deserve it and wanted it a ‘surprise; Matt Smith for one

has a theory that he’s a future Doctor in the same way Tom Baker sort-of is in

‘Day Of The Doctor’) waxes lyrical about how

Van Gogh is the greatest ever painter who turned his suffering into joy for

others and the painter finally gets the acceptance he’s missed all his life, a

scene played impressively low key and straight without the usual Murray Gold

choir. Even though it’s typical of this story that it follows on from a

horrifically overblown scene full of hyperbole that features a most

inappropriate song (‘Chances' by the band ‘Athlete’ that doesn’t fit at all)

and that a man who’s dedicated his life to art doesn’t recognise the man

standing in front of him (and who’s dressed just like his ‘self portrait’ just

to rub it in!)

The mental illness is well handled too for the most

part, another aspect of the episode close to Curtis’ heart (as his sister died

young from suicide). For the first half it very much isn’t: Van Gogh is too

stable, too nice, too stable, too ‘ordinary’ and we’re so clearly on his ‘side’

that when the locals start attacking him, blaming his madness on a child found

dead, it seems obvious that they’re wrong and he’s right. But then something

clever happens: he starts fighting off monsters we can’t see. Neither can The

Doctor. He glances at Amy and they both think he’s having a fit. Only later do

they find out that he’s fighting an invisible monster they can’t see (and while

there’s no scripted reason Van Gogh should see one where others can’t Curtis

cleverly weaves in the overall theme that artists see the world differently,

such as the episode’s third best scene, the coda where the trio are lying in

the grass and he makes even The Doctor view the stars in a whole new way). For

the most Van Gogh stabilises himself, but then The Doctor nags him into painting

one time too many and he collapses, in agony, on his bed, convinced he’s a

fraud and he’ll let everyone down. It’s a brilliant scene (the second best):

The Doctor immediately turns into patronising mode, trying to gee him out of

bed but Van Gogh roars at him to be left alone and the Doctor panics: all his

many hundreds of years of experience and he has no way of comforting a man in

this much pain. So he leaves, defeated, even though it means the monster will

win. Of course they undo it by having Van Gogh recover remarkably quickly but

the fact that they go there, the fact they acknowledge that sometimes hurt goes

too deep for even The Doctor to help, is a brave risk they didn’t need to take.

The fact that Curtis refused to stick in any jokes or even a mention of Van

Gogh cutting off his own ears helps a lot too: Van Gogh is treated with a lot

more courtesy, love and respect than almost any other similar figure in the

series (only Dickens in ‘The Unquiet Dead’ comes close). The fact that this

becomes the one Dr Who story that came with its own helpline number (for The

Samaritans, sadly cut from the DVD, blu-ray and i-player editions) shows just

how seriously people were taking this, as indeed they should.

The really frustrating part, though, is how

inconsistent the portrayal of madness is and how they nearly went further

still, but bottled it. We didn’t have full proper mental health diagnosis in

1890 but it seems likely that Van Gogh was bipolar in the days when there were

no tablets to help stabilise moods. He shouldn’t be this ‘normal’ for most of

the story, he should be either manic or crushed. It’s amazing how quickly he

recovers when the script needs him to. The story also skimps on the real

horrors of Van Gogh’s life; at this point he’s only recently out of a mental

asylum (his famous ‘Starry Night’ was painted from the asylum window, dreaming

of escape and the joy in the stars outside (a painting so beloved of Dr Who

fans a Tardisified version was on everything in 2010, including some underpants

with a most unfortunate placement of the series arc ‘crack’. Though still not

as bad as where Tom Baker’s face used to be on the notorious 1970s Dr Who

underpants). These asylums aren’t like they are now, with sympathetic

therapists and home comforts (if you’re lucky anyway) but awful places where

you were basically locked up and starved, quite possibly with members of the

public laughing at you.When he got out Van Gogh was living off charity and kept

by family and friends – watching the episode gives you the impression that Van

Gogh was alone but he really wasn’t. However the family and friends had to pay

because there was no welfare state to keep Van Gogh both alive and painting.

The frustration was he’d had a bright start as a painter, accepted into a

prestigious French academy, but his mental health saw him drop out and feel

unable to keep out. He should feel the pressure The Doctor puts on him even

more than he does. This episode over-ran badly admittedly but there are some

really powerful lines by Curtis that they seem to have chickened out of,

replaced by a softened diluted version that’s not as strong, the best one being

Amy wondering how someone that talented should be so unsure of themselves and

The Doctor answering ‘The mind is a terrible enemy, Amy. You should pray your

life is full of cuts and bruises and blood and bone – that’s the easy stuff.

Pain in your mind, that’s the worst pain there is’.

The story goes to great

lengths to show that Van Gogh isn’t mad, just troubled. Unfortunately the script

suggests it’s all a result of being seen as a failure, compounded by seeing

monsters. That just isn’t true. Van Gogh had a horrible last year of his life,

barely touched on in the episode: his brother Theo, who’d protected him through

thick and thin, withdraw his financial support over a spat on how recklessly

Van Gogh was spending his cash. Theo also happened to be his art dealer: while

you could argue Vincent would have been better off with someone who could sell

more than a single painting in his lifetime anyway, he thought that was his

last chance of anyone ever seeing his art. That’s why he killed himself really,

the last straw that pushed him too far. not anything that happens in this

story. The thing is though...he can see aliens. Aliens that no one else can

see. At a time when people didn’t speak about aliens, but demons. Not only

that, he adds them to the windows of his paintings so other people can see them

as well. Frankly anyone around in 1890 who didn’t see that as madness was

probably mad themselves. It’s never properly explained why Van Gogh can see

what other people can’t. The closest explanation we get is ‘because he’s a good

painter’ but being a great artists doesn’t give you super-powers of alien

detection however observant you are. I like to think there’s a parallel

adventure going on round the corner, only the guy or gal who painted aliens

couldn’t draw them for toffee and everyone thought they were a bowl of fruit or

something. Or even better a surrealist or cubist or pop-artist (we like your

tins of soup Mr Warhol, but why is there a Krafayis tucking into one of them?!)

especially as the aliens turn out to be of the conveniently invisible for most

of the story. It all seems a bit desperate and the two plot strands are never

brought together satisfactorily.

This is also one of those stories that would have

been far better without a monster in it, for if ever a Dr Who monster were perfunctory its the Krafayis, which are

barely seen or heard from throughout; odd given that the Doctor recognises them

‘from the dark times’ and thus they’re one of the few deeply powerful creatures

he knew about in childhood before leaving Gallifrey. The

krafayis cheapens the rest of the story, a mostly invisible creature (although

we do see it in the Doctor’s gadget’s mirrors – it looks like a close cousin of

the editor in ‘The Long Game’) that got left behind by a hunting pack. The idea that the krafayis got separated from the

others of their kind and is blind (well, somebody had to lose a body part in a

story about Van Gogh, which was set before he chopped off his ear) is a neat

twist on the usual sort of Who monsters but why they’ve chosen the outskirts of

19th century Paris to land in or how they can track down humans at all when

blind is never explained. There’s a half hearted attempt to have

it be a metaphor for depression, a monster that only certain people can see,

but it’s clumsily handled. After all, this is a ‘real’ beast that’s physically

there, not a delusion of a confused mind. Few if any people suffering from mental health would compare it to a

dinosaur/bird hybrid that does physical damage to objects, that’s just silly;

if that’s really what people were going for – rather than what they decided

after the event – they’d have done better to make it a shadow, like the Vashta

Nerada or Churchill’s ever-present black dog, like the Garm or Karnavista but

less benign. Van Gogh identifies with the creature because he sees

it as an outsider left behind, one who lashes out the same way villages do to

him because he’s scared, which would have been a stronger place to go. But he

helps kill the creature all the same, with his easel acting like a stake in a scene that’s pure farce, the

sort of low budget wave-the-camera-at-nothing-and-fall-over Dr Who nonsense we

thought we’d never have to sit through again in the new big(ish) budget series,

a scene

that’s straight out of the Chuckle Brothers and played for giggles throughout. As fun as it is to watch Tony Curran, Matt Smith

and Karen Gillan chasing an invisible monster wreaking havoc around an empty

French villa, it’s so out of place as to seem like Dali added a coat of varnish

over the top of one of Van Gogh’s pieces. It would have been so much stronger

had they dispensed with the scifi trappings altogether and made this a pure Dr Who

historical like the early days, the ones where the real monsters are humans

whose motivation is ignorance not corruption and the people attacking Van Gogh

because they don’t understand or appreciate him.

Mostly though the problem with this script is the

beginning, with Amy at her most uncharacteristic, as she enthusiastically joins

The Doctor in a trip down the local art gallery. Had Rory been along for the

ride (instead of remaining dead) it would have made more sense but this is Amy:

culture is not her strong point. The Doctor then just happens to notice an

alien in a painting window that we know for a fact isn’t in the real one

(admittedly Van Gogh does paint it out later) and which he’s never noticed

before. Well, that’s a whacking coincidence isn’t it? To be fair this opening

is the biggest casualty of the episode over-running: there should have been an

entire scene of Amy asking The Doctor if he was ever scared in his childhood

and jokingly asking if he had a tiny teddy bear (to which he replies ‘I did,

but he was huge – and had four ears!’) before The Doctor remembers a scary

monster from an old fairytale, the Krayfayus. He then asks The Tardis for a

copy of the tale, only to accidentally find out that the creature is real – and

when he asks for visual proof sees Van Gogh’s painting (in reality it was Van

Gogh’s daughter Scarlett who suggested the church painting as the sort of place

a monster would hide). The scene then goes on to have The Doctor tell us he’s

come across this sort of thing before, adding that ‘The Nightmare’ by Fuselli

actually features a ‘Praxis’ (years before there was an episode called that),

that Bosch’s ‘Hell’ is a vision of a real place he went to ‘and had two very

bad holidays in’ and that the subject of Munch’s ‘The Scream’ was disturbed by

an alien they were staring at! Not the most convincing start to a Who episode

perhaps – and proof of how little Curtis had seen of the series when he started

writing – but at least it makes a sort of sense, which is one hell of a lot

more than the version that made it to TV does.

The most off-putting scenes, though, are the ones

where Curtis remembers he’s best known for writing romantic comedies and writes

both Vincent and Amy as being very flirty. This is a nonsense and not like the

real Van Gogh at all (he was shy of most people but especially girls. He’s a

rare named painter who did figures yet never drew the female form though there

are lots of boys. The closest he got to a date was a girl who’s family barred

her from ever seeing him very early on, a prostitute and his own niece!) The

dialogue between them is excruciating: all that talk about their children

having very ginger hair gets old quick and is incredibly stilted. ‘Your hair is

very orange’ ‘So is yours’ might just be the worst chatup line in Curtis’ back

catalogue. And I’ve sat through ‘Love Actually’! It also makes the audience

uncomfortable: we know, what Amy doesn’t, that she was due to get married to a

boy who just got wiped out of existence. Fair enough iof she can’t remember him

in the moment but her subconscious clearly remembers (hence Van Gogh’s talk

about her understanding grief and asking why she’s crying; does he not think of

asking if she has a boyfriend and whether that’s who was lost?) The Doctor

never intervenes, if he accidentally says Rory’s name at one point – Amy

doesn’t pick him up on it. You

wonder what Amy thought about this fling once the timelines came back together

again and she remembered Rory, but I guess you can’t get into trouble for

double dating when you’ve had your memory of the first love wiped! You suspect that Rory would never have forgotten

Amy though, if things were the other way around and he was in a story with, say

Marilyn Monroe.This all maybe wouldn’t seem so bad had

we not just seen Rory killed in the closing moments of last week’s story and

spent the whole episode waiting for him to come back (we weren’t to know he’d

be ignored till the finale).

Another is the casting of

Tony Curran who gives one of the best performances of any cast part in the

series’ long history (again despite our fears when he was announced. I mean, a

Scottish Van Gogh, I thought that would never ever work, but it does!) This is

a hard part to get right and even more with the script being so inconsistent

but Curran both looks the part (most films about paintings and painters hide

the real things, to help us ‘forget’ how wrong the actors and actresses look –

thinking of you ‘Mr Turner’ and ‘Girl With A Pearl Earring’ – but Curran is so

close to the real thing it actually lead to a last minute re-write using Van

Gogh’s genuine self portrait to show off how close he really is) and acts it, a

bravura performance where he nails every last quirk of the painter. It would

have been easy to make him a pitiable figure, unloved and unlovable and

borderline insane, but instead Curran grasps the love and awe that’s in Van

Gogh’s paintings. The fact Curran can talk about how glorious it is to be

alive, a few days before his suicide, and sell the fact that he genuinely means

it, before finally releasing all those pent-up tears on hearing how loved he

is, goes a long way to making this story’s last act so moving and powerful. Bill

Nighy too really makes the most of his cameo, dressed the way Matt Smith’s

Doctor does complete with bowtie as an extra joke on the people who

traditionally dress like that (art teachers). We don’t see many other

characters but what little we do see is well handled too, contrasting what we

at home think of Van Gogh (as a brilliant artist) with how the people in his

life see him (as a dangerous mooch who’s never going to amount to anything). As

for the regulars Karen Gillan struggles with the rather weird mix of wide-eyed

innocent naive girl nd adult flirt that Curtis has given Amy but Matt Smith is

given material that fits him best: a sympathy for the under-dog and moments of

panic and guilt in between epic clowning (although I suspect Moffat had a hand

in adding a lot of those parts, as all of Curtis’ draft scripts were handed

back and asked to make the Doctory less solemn or pompous and more ‘Doctory’).

The end result is a nice mix though: at times the Doctor is every bit as

eccentric as Van Gogh and possibly more so; at other times though he’s our link

to sanity and the moral champion of the underdog the character always was at

his best.

The result is one of

those stories that generally rates highly in modern episode polls and

deservedly so – it’s a real risk of an episode, bringing to life a person from

the past who’d maybe not as immediately known to a family audience and led a

difficult and troubled life, portraying it without flinching. The scenes that

everyone remembers are rightly talked about in revered tones because they go

for the jugular: the villagers chasing our hero for no other reason than he’s

mad and they’re scared of him; Vincent getting his applause at last, 100 years

too late but better than never at all in a glorious scene that brings a tear to

the eye of anyone who’s ever ‘failed’ at doing something they love; Van Gogh

pointing out the way the light in the sky brings him hope in a way that means

you’ll never look up at it the same way yourself. It’s the scenes in between

that fall flat and are unworthy of this episode’s high reputation with clumsy

dialogue and clumsy comedy scenes that really should have been cut (especially

as a lot of the stuff that was cut is needed to follow the story and works far

better). I had hopes this story was going to lead to a whole run of stories

like this one (I’d love to see The Doctor meet Turner, a Doctory eccentric if

ever there was one, returning him from the ‘establishment figure’ he’s treated

as today to the working class rebel breaking the laws and fighting the system

as hard as he can, or granting comfort to another unstable genius way beyond

their lifetime like Syd Barrett or Brian Wilson) but maybe it’s better that

this story remains a one-off, undiluted by copycat tales. For the most part it’s

a worthy tale by a writer who didn’t need the Dr Who gig to pay the bills or

advance his career but felt it was a worthy place to tell a very grown-up tale

of hardship and illness. For the most part it’s treated with due reverence and

care by a production team and cast who realise how important this story is and ends

up a story not just about one man’s struggles to make his mark but gives all of

us, struggling with the idea of failure in our lifetimes, hope that the future

might be kinder than the present. This is an episode that (mostly) does a

complex man proud within forty five minutes – a tough ask for any writer – and brought

a lot of hope to a lot of people struggling to find their way and there aren’t

many episodes of a TV series, even this TV series, that can do that. The

episode is also, you suspect, one that Dr Who’s original creator Sydney Newman

would have liked most, a powerful story that says something deep that allows a

writer to pour their love for their subject through th screen, like the

original David Whittaker-scripted days: I can’t say I’ve ever rated Van Gogh

that highly as a painter but seeing him through Curtis’ eyes and especially the

curator’s passionate speech at the end made me see him in a ‘new light’. And

new lights are what the episode is all about, seeing things in a different way

from monsters to mentally ill painters who won’t pay their bills. Despite never

seeing Dr Who before 1999 Curtis really nailed that aspect of the series. When

this story was first announced I thought Curtis’ saccharine combined with Moffat’s

love of fairytales and happy-ever-afters would make something

teeth-shatteringly saccharine but instead its impressively dark, far more than

it needs to be, with only the attempts to give this story shade that let it

down. Moffat, the story’s biggest critic when it was first pitched to him an

the first draft came in (he spent his life asking commissioned writers to have

a first meeting between central characters ‘just like a Curtis film’ and was

embarrassed when he had to keep sending the script back, asking for ‘more of

what you usually do’ when The Doctor and Vincent meet; it’s still a rather

clumsy and awkward scene) but changed his mind enough to call it the favourite

of his era’s episodes when he handed over to Chibnall seven long years later.

The end result is still at least a draft away from being the full-on classic a

lot of fans would call it, with problems galore, but as the script puts it the

bad parts don’t make the good parts shine any less and it’s a brave stab at

doing something really important that ever so nearly comes off.

POSITIVES + The art department

excel themselves with the re-creations of Van Gogh’s paintings, from the

Krafayis perched at the top of the painting ‘The Church Of Auvers’ to the

depiction of the broken Tardis in Van Gogh’s style to come in season finale

‘Big Bang’, which has deservedly become a popular picture amongst Who

followers, on everything from tote bags to mobile phone cases to underpants.

‘Sunflowers’ and ‘Van Gogh’s Chair’ are also brilliantly re-created s real

props too while the dialogue makes good use of ‘A Starry Night’ (a much more

obvious painting for a scifi plot than ‘Church At Auvers’ - wouldn’t it have

been better for Van Gogh to have drawn a ufo in that panting instead?) ‘Auvers’

is by coincidence more than knowledge one of Van Gogh’s last paintings though

and scholars say it’s darkened skies and ominous clouds point to a turn in the

painter’s mental health (usually there’s some hopeful light in there

somewhere). The church is still standing today by the way and really doesn’t

look much at all like Llandaff Cathedral.

Previous ‘The

Hungry Earth/Cold Blood’ next ‘The Lodger’

No comments:

Post a Comment